What Cranberry Restoration Teaches Us About Gratitude

Plus: Resources Highlighting Native American Voices

This Thanksgiving week, I can’t stop thinking about cranberries and what they’re teaching us about second chances.

You know those cranberries sitting on your table Thursday? In Massachusetts, they’re not just food, they are a $1.7 billion industry.

For more than 150 years, families on Nantucket and across the state have coaxed these ruby berries from sandy soil that barely grows anything else. The Wampanoag people harvested them for thousands of years before that. Cranberries are woven into the fabric of this place.

But something to discuss at your Thanksgiving dinner is how some of those bogs are dying. Not because the farmers failed. Because the world changed on them.

You see climate change doesn’t give a damn about tradition. Those cranberry plants need cold winters to bloom and crisp fall nights to turn that perfect red. But Massachusetts now feels like New Jersey, maybe even Delaware. Early springs trick the plants into blooming too soon, and late frosts kill those premature blossoms. New insects and fungi move in.

At Windswept Bog on Nantucket, cranberries thrived for a century. It’s a spot that holds 100 years of family knowledge, calculated flooding and draining, and harvest seasons that brought the community together. In 2018, the Nantucket Conservation Foundation had to make a choice that would’ve broken hearts 30 years ago. They had to shut it down.

Here’s where it gets interesting and even hopeful.

Instead of abandoning those 40 acres to become a wasteland, they decided to give the land back to itself. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Massachusetts Division of Ecological Restoration, and others stepped up with money to make it happen.

They ripped out 2,500 feet of berms, removed 28 water-control structures, filled in ditches, and hauled away a one-to-three-foot layer of sand that had accumulated. They “roughened up” the surface to wake up native wetland plant seeds that had been lying dormant in the soil, waiting.

“Setting the stage for nature to come in and take over and do the rest of the work... it’s really awe-inspiring,” Karen Beattie, vice president of science and stewardship at the Nantucket Conservation Foundation said. “I’m looking forward to seeing how the site responds.”

Talk about wisdom.

What We Get Back

Let’s talk about return on investment. Let me tell you what a functioning wetland gives you that a failing cranberry bog doesn’t.

Clean water. Before restoration, Windswept was a highway for pollutants, such as fertilizers, bacteria from septic systems, road runoff, all flowing straight into Polpis Harbor and Nantucket Harbor. That pollution was killing the scalloping and boating industries. A natural wetland helps filter that out.

Climate resilience. Wetlands absorb storm surge. They buffer waves. With sea levels rising, saltwater is predicted to reach Windswept’s northwestern edge by 2100. That restored bog will give salt marsh habitat, which is becoming scarce, somewhere to migrate as it retreats from rising seas.

Carbon capture. Wetlands lock up massive amounts of carbon dioxide in their soil. Massachusetts needs every tool in the toolbox to meet net-zero emissions goals. These restored bogs are climate warriors.

Wildlife habitat. They tracked turtles at Windswept with radio transmitters during restoration. Data showed the animals were active there in the spring, summer, and fall and traveled to nearby wetlands to hibernate in winter. Birds, fish, amphibians; they all need these spaces.

The Bigger Picture

Massachusetts has already restored nearly 500 acres of wetlands with 17 more projects in the pipeline. They’re on track to restore 1,000 acres of cranberry bogs in the next decade.

Since 1992, the National Coastal Wetlands Conservation Grant program has contributed more $530 million to conserve and restore 600,000 acres of wetlands. That money comes from taxes on fishing equipment, boat motors, and recreational fuel. How cool that the people who love the water help pay to protect it.

Gratitude as Action

This Thanksgiving, yes, I’m grateful for cranberry sauce. But I’m more grateful for the people who had the guts to admit when something wasn’t working anymore, and the vision to imagine something better.

“These projects will transform degraded former cranberry bogs into thriving wetlands that will provide habitat to important species, flood control in time of storms, and access for all to beautiful natural areas,” Governor Maura Healey said in a statement.

I’m grateful that we’re finally understanding something Indigenous peoples knew all along. Sometimes, the most powerful thing you can do is get out of the way and let the land heal itself.

Those cranberry bogs served Nantucket for more than a century. The restored wetlands will serve it for centuries more.

Sometimes, moving forward means getting back to our roots. Progress means restoration. Sometimes, the bravest thing we can do is admit that what worked before isn’t working now—and choose transformation over stubbornness.

The land remembers what it’s supposed to be. We just have to give it the chance.

Happy Thanksgiving. Now pass the cranberries and remember where they came from.

Native American Heritage Month is celebrated each November, as a time to celebrate the traditions, languages, and stories of Native American communities and ensure their rich histories and contributions continue to thrive.

Yes, Thanksgiving is a time to celebrate everything we are grateful for and get together with loved ones for a feast. Many of us learned the Thanksgiving story that involved Pilgrims and Indians sitting down to a happy meal together and becoming fast friends.

The harvest celebration of 1621 was not actually called Thanksgiving. The next official “day of thanksgiving” was after settlers massacred more than 400 Pequot men, women, and children. Learn more here.

Here are a few resources to help you celebrate and honor the Native American experience.

Watch

An investigation into Native American filmmaker Sterlin Harjo’s family history, namely the mysterious 1962 disappearance of his grandfather and the songs of encouragement sung by those who searched for him.

This documentary brings to light the profound and overlooked influence of Indigenous people on popular music in North America. Focusing on music icons like Link Wray, Jimi Hendrix, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Taboo (The Black Eyed Peas), Charley Patton, Mildred Bailey, Jesse Ed Davis, Robbie Robertson, and Randy Castillo.

Read

There, There by Tommy Orange is a novel that grapples with the history of a nation. After noticing a lack of stories about urban Native Americans, Orange created a remarkable work that explores those who have inherited a profound spirituality, but who are also plagued by addiction, abuse, and suicide.

This book was a finalist for the 2019 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and received the 2019 American Book Award. In October 2025, Orange was awarded a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship. Orange is a citizen of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma.

Since 1984, Louise Erdrich has established herself as one of the most prominent and decorated authors in literature thanks to her thought-provoking, intricately written books.

Inspired by her grandfather, Erdrich’s sixth standalone novel The Night Watchman is a fictionalized version of his fight to resist the Indian termination policies of the 1940s and 1960s. An undeniably powerful work that grapples with the best and worst of human nature, Erdrich captivates readers’ minds and hearts with great ease. Critically acclaimed, the novel earned her the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

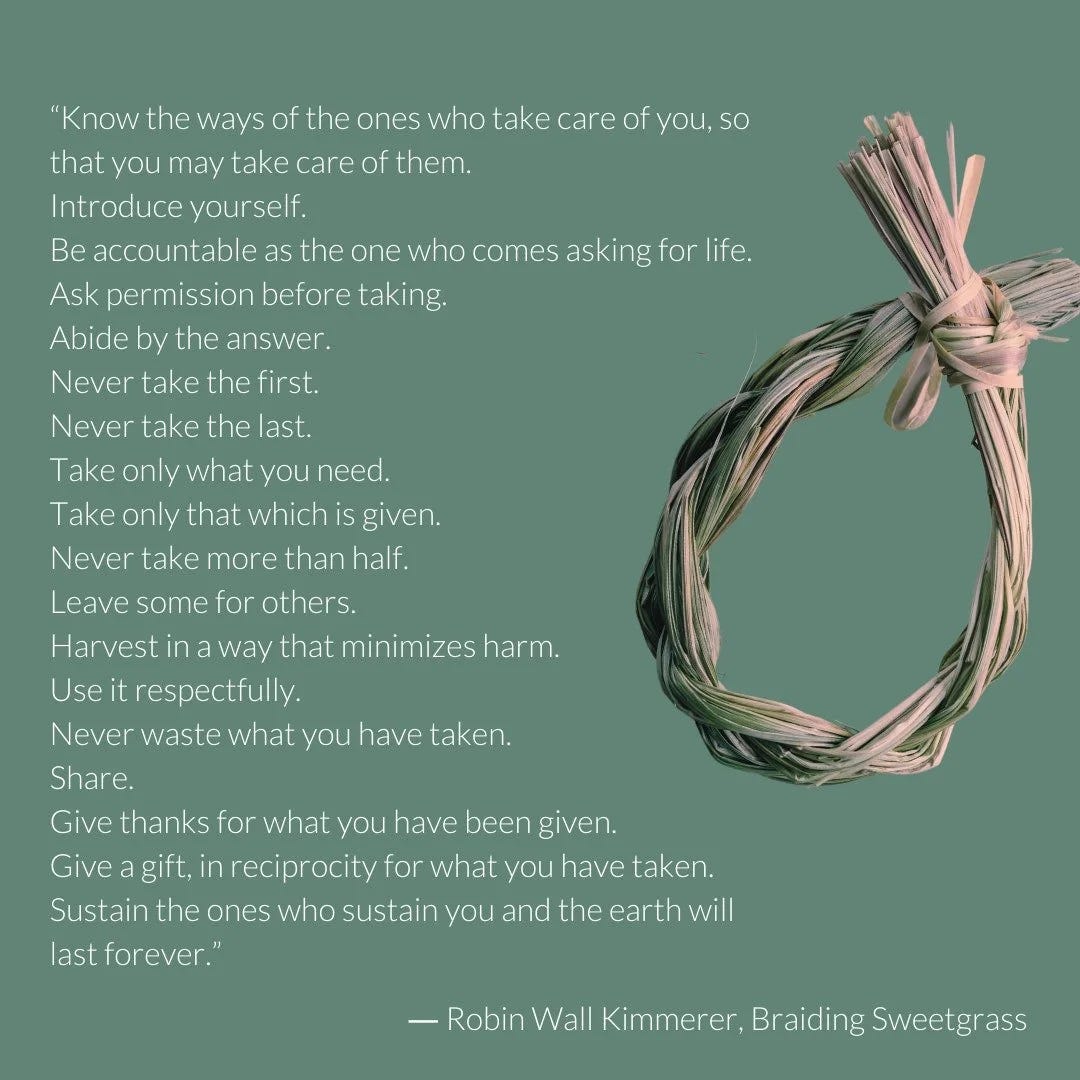

Biologist and author Robin Wall Kimmerer shares the importance of being a voice for ecological justice and the need for all of us to recognize our individual gifts and responsibilities.

She is a mother, plant ecologist, and Distinguished Teaching Professor at the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF) in Syracuse. She is also founding director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment. Interested in the restoration of ecological communities and the restoration of our relationships to land, she draws on the wisdom of both Indigenous and scientific knowledge to help us reach sustainability goals. For Kimmerer, however, sustainability is not the end goal; it’s merely the first step of returning humans to relationships with creation based in regeneration and reciprocity.

Listen

Charly Lowry is a dynamic singer-songwriter from Pembroke, North Carolina. She is proud to be an Indigenous woman belonging to the Lumbee and Tuscarora Tribes. She considers her work a platform for raising awareness around issues that plague underdeveloped and underserved Native communities.

Multi-award-winning musician Martha Redbone is one of the most vital voices in American roots music. This charismatic songstress sings a tasty gumbo of roots music embodying both the folk sounds of her childhood in the Appalachian Mountains of Kentucky and the eclectic grit of her teenage years in pre-gentrified Brooklyn. In her performance, Redbone embraces her identity as Cherokee, Chocktaw, European and African-American, and enchants the audience in her musical journey.

Keep the conversation going in the comments below. Did you know the significance of cranberry bogs and wetlands? What traditions do you bring to your Thanksgiving table?