What A Waste!

Hazardous Fire Debris Does Not Belong In A Neighborhood Near Schools and Homes.

Never ever underestimate the power of a pissed off mom. When you mess with their kids’ health and their community, they will organize, and they will fight for justice.

When Kelly and Natasha reached out for my help last weekend (with a sweet baby in tow), I knew I needed to listen and use my platform to help elevate their cause.

They are part of a larger group (www.protectcalabasas.org) trying to protect their community from receiving thousands of tons of debris per day as part of a massive cleanup operation following the devastating Los Angeles County wildfires last month.

Calabasas, California, is a town in the foothills of the Santa Monica and Santa Susana mountains about 30 miles northwest of downtown Los Angeles. It’s also a community with a residential landfill. The Calabasas Landfill sits within a one mile radius of six schools, close to playgrounds, parks, and thousands of homes.

"We are just a bunch of moms looking to protect our kids, our schools, our health, not wanting this to become some huge thing in 20 years when a bunch of kids are sick and we have to sue for damages," Kelly Rapf Martino told the Los Angeles Times. "We're trying to stop that before that happens."

No one wants toxic waste in their backyard.

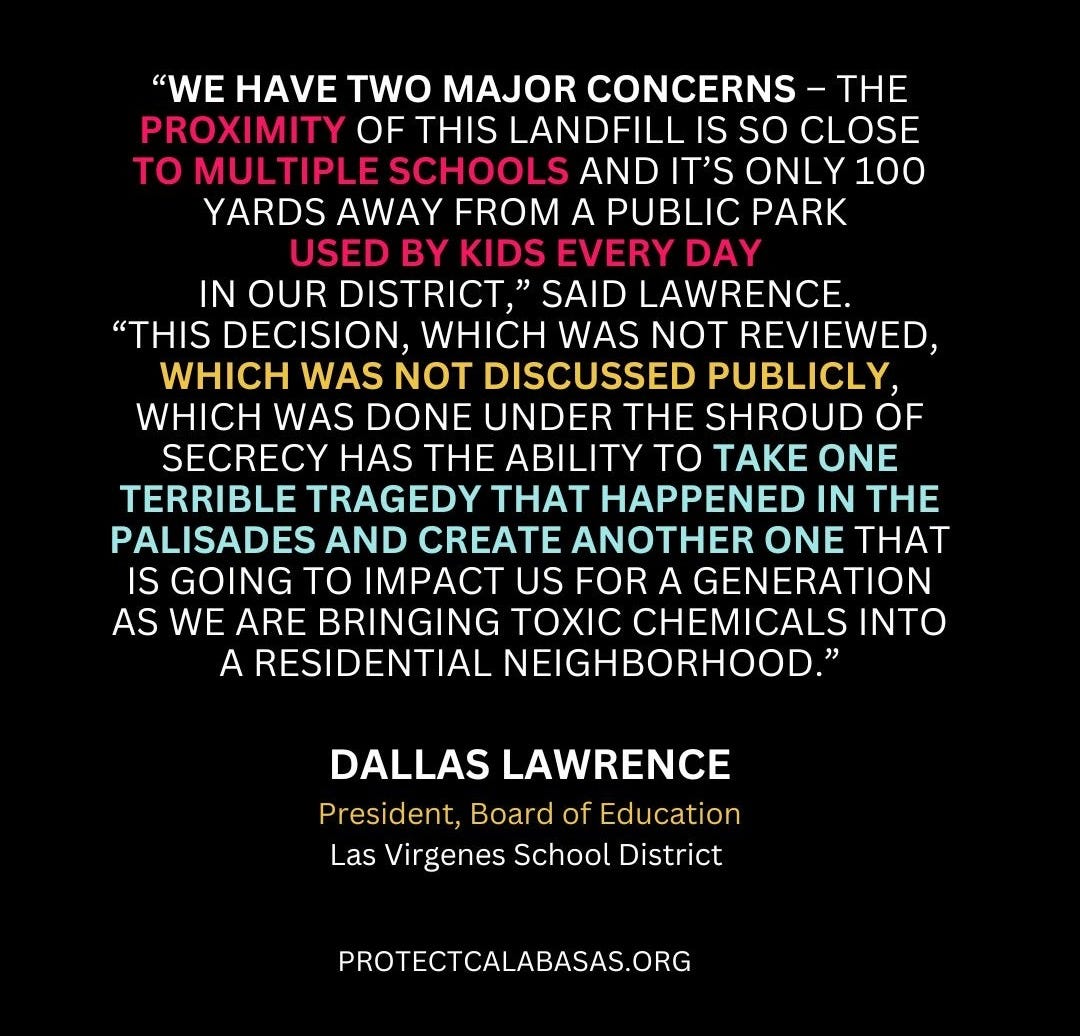

Los Angeles County made this decision without giving residents notice, without a city council vote or community discussion, and without testing the debris, which could be full of harmful lead, asbestos or arsenic, as well as newer synthetic materials. If older homes had carpets or rugs, they may have contained PFAS.

I talk about this issue all the time. We need transparency from our elected officials. Decisions like where to put tons of toxic debris should not be made in secret.

The Eaton and Palisades fires destroyed more than 9,400 structures in Altadena and more than 6,800 in Pacific Palisades. While my heart breaks for everyone who lost a cherished home in those fires, we cannot swap one tragedy for another.

The toxic leftovers from these fires threaten not only the land but also the drinking water and the air. It could create a toxic legacy for the families that live nearby for generations to come.

The City Council for Calabasas sent a letter of opposition to the County of Los Angeles Board of Supervisors on February 14, expressing concern over the proposed course of action. Read the letter here.

The council met for a special meeting on Monday and with a unanimous vote, authorized the City Attorney to file a writ petition, including a temporary restraining order, to enjoin the Los Angeles County Sanitation District and Los Angeles County from receiving any fire debris material at the Calabasas Landfill, based on the concern that the debris will contain hazardous materials.

The City Council is also planning to attend the County of Los Angeles Board of Supervisors meeting on February 25 at 1 p.m. to express their opposition to the decisions being made. Residents are encouraged to submit public comments here.

To further express the community's opposition, the City is renting a bus to bring participants to the meeting, in-person, at the Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration in Los Angeles. Seats are available on a first-come, first-serve basis. To sign-up, click here.

Waste is a growing problem—even without devastating disasters that create hazardous debris.

The immense quantities of waste that need to be processed each day require communities to develop new infrastructures for processing and disposal, which are often beyond the resources available.

Landfills are regulated under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) Subtitle D (solid waste) and Subtitle C (hazardous waste) or under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA).

The EPA does not maintain a list of all the landfills in the United States, but estimates say we have about 3,000 active landfills and 10,000 closed landfills. Studies like this one and this article indicate that residents living closer to landfill sites have higher health risks when compared to those living further away from them.

Landfill 101

Subtitle D (solid waste) focuses on state and local governments as the primary planning, regulating, and implementing entities for the management of nonhazardous solid waste, such as household garbage and nonhazardous industrial solid waste.

They include:

Municipal Solid Waste Landfills (MSWLFs) – Specifically designed to receive household waste, as well as other types of nonhazardous wastes.

Bioreactor Landfills – A type of MSWLF that operates to rapidly transform and degrade organic waste.

Industrial Waste Landfill – Designed to collect commercial and institutional waste (i.e. industrial waste), which is often a significant portion of solid waste, even in small cities and suburbs.

Construction and Demolition (C&D) Debris Landfill – A type of industrial waste landfill designed exclusively for construction and demolition materials, which consists of the debris generated during the construction, renovation and demolition of buildings, roads and bridges. C&D materials often contain bulky, heavy materials, such as concrete, wood, metals, glass and salvaged building components.

Coal Combustion Residual (CCR) landfills – An industrial waste landfill used to manage and dispose of coal combustion residuals (CCRs or coal ash).

Subtitle C (hazardous waste) establishes a federal program to manage hazardous wastes from cradle to grave.

They include:

Hazardous Waste Landfills - Facilities used specifically for the disposal of hazardous waste. These landfills are not used for the disposal of solid waste.

Polychlorinated Biphenyl (PCB) landfills - PCBs are regulated by the Toxic Substances Control Act. While many PCB decontamination processes do not require EPA approval, some do require approval.

PFAS In Landfills

Many toxins are a concern for landfills, but PFAS pollution is a known problem at landfills throughout the U.S., demonstrating the importance of monitoring and testing at these sites.

Experts estimate that about 16,500 pounds of PFAS end up in landfills each year from discarded household goods, industrial waste, and more. About 1,100 pounds of these chemicals get released, creating air pollution problems for people living nearby.

Another 1,760 pounds of PFAS escape through liquid waste called landfill leachate, contaminating groundwater and drinking water. At some landfills, PFAS are detected at levels in the tens of thousands of parts per trillion, or ppt, which is dramatically higher than the 4 ppt drinking water limit the EPA has established for six PFAS.

Some examples from across the country:

Minnesota officials found PFAS in 100 closed landfills, including 16 sites where PFAS detections were 10 times above state drinking water standards for the chemicals.

New Hampshire officials found that 135 out of 174, or 77.5 percent, sampled landfills had PFAS in groundwater above state standards.

Vermont officials found elevated levels of several different PFAS in the leachate of all landfills tested.

California officials found the leachate at 84 sampled landfills contained PFAS. At some sites individual PFAS were found at tens of thousands ppt.

Michigan officials have identified 93 landfills where PFAS have been detected.

Researchers in Washington state found elevated levels of PFAS in 17 sampled landfills.

New York officials found PFAS in the groundwater above state standards at 70 percent of inactive landfills surveyed.

More than 13 million people live within one mile of a landfill. Cancer is more prevalent among communities living near landfills.

Protect Calabasas has another protest happening later today. Get all the details here.

I stand with the mothers and the community of Calabasas. This fight is not just another environmental incident. It is a opportunity for all of us to learn more about landfills, get engaged with local governments, and lead the conversation for more responsible waste management.

Have something more to add to the conversation? Let us know in the comments below.