The End of Forever Chemicals?

The EPA Has (FINALLY) Issued National, Legally Enforceable Drinking Water Standards For PFAS.

Last week, the EPA finalized and issued the first ever enforceable federal limits for six types of PFAS in drinking water systems.

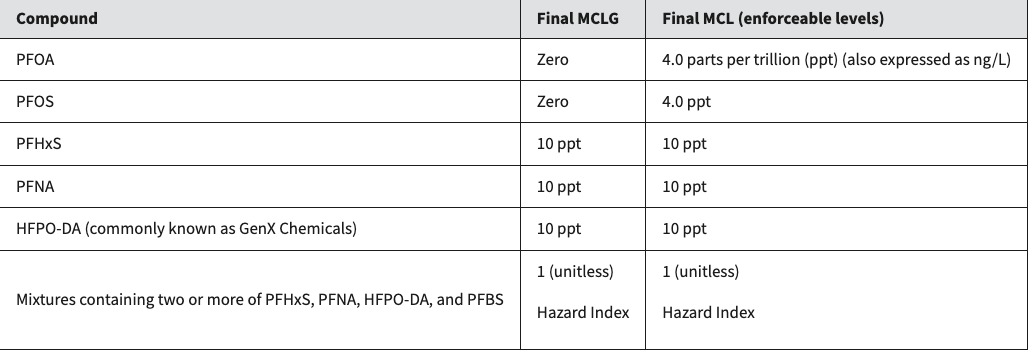

The limits now sit between 4 and 10 parts per trillion for PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS, PFNA and GenX. To understand that measurement, it’s less than a drop of water in a thousand Olympic-sized swimming pools. The sixth type, PFBS, is regulated as a mixture using what’s known as a hazard index.

To inform the final rule, the EPA evaluated more than 120,000 comments submitted by the public on the rule proposal, and considered input received during multiple consultations and stakeholder engagement activities held both prior to and following the proposed rule.

The agency estimates that the final rule will prevent PFAS exposure in drinking water for approximately 100 million people, prevent thousands of deaths, and reduce tens of thousands of serious PFAS-attributable illnesses.

Tens of thousands of drinking water systems across the country have never tested for these contaminants.

In addition to the final rule, the EPA also announced nearly $1 billion in newly available funding through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to help states and territories implement PFAS testing and treatment at public water systems and to help owners of private wells address PFAS contamination.

This is part of a $9 billion investment through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to help communities with drinking water impacted by PFAS and other emerging contaminants, the largest-ever investment in tackling PFAS pollution. An additional $12 billion is available through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law for general drinking water improvements, including addressing emerging contaminants like PFAS.

It’s been a long road to get here. Our first ever article for this newsletter was about a huge PFAS problems in Maine.

These substances were invented in the 1930s by chemists. They can be found in the blood of most Americans and in many drinking water systems.

In 2009, the EPA published provisional health advisories for per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), also known as forever chemicals, based on the scientific evidence available at that time, which was considered “inconclusive.” In those days, the MCL was 400 parts per trillion (ppt) for PFOA and 200 ppt for PFOS.

By May 2016, the EPA significantly lowered the “safe levels” for these pollutants in our water supply, based on standards that assumed lifetime exposure to rather than drinking these chemicals for only a few weeks or months. The new health advisory for PFOA and PFOS was set to 70 ppt. Those standards created instant water contamination crises for many cities and towns—14 systems exceeded the federal threshold for PFOA and 40 systems were above the limit for PFOS.

Those advisories still came years and years after the agency was first alerted to PFOA contamination in the drinking water near DuPont’s Teflon plant in West Virginia. People were exposed for years at the higher level before a new advisory was issued and it was still not an enforceable one.

For years, more information has surfaced that the companies who made these substances knew about their health impacts decades ago. In 2010, the Minnesota Attorney General and the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources filed a $5-billion lawsuit against 3M, headquartered in Maplewood, for damages to the environment.

The lawsuit claimed that 3M released its perfluorochemicals (PFOS and PFOA) into the nearby groundwater and in 2004, the chemicals were detected in the drinking water of 67,000 people in Lake Elmo, Oakdale, Woodbury, and Cottage Grove.

While the company tried to argue that no health effect to humans had ever been proven, documents released in the case showed that 3M researchers knew these chemicals could bioaccumulate in fish and that the compounds were toxic. 3M settled the suit for $850 million in 2018, and afterward the Minnesota Attorney General’s Office released many internal documents including studies, memos, emails, and research reports, showing how much 3M really knew about these chemicals and their harm to both people and the environment.

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry released a draft report in June 2018 discussing how people are exposed to these chemicals and the health risks they pose. The agency found that these chemicals are particularly damaging to vulnerable populations, such as infants and breastfeeding mothers at levels lower than what the EPA deemed safe in the 2016 health advisory.

FYI: we have enforceable and non-enforceable drinking water regulations.

Of the enforceable regulations, we have what’s called Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs). An MCL is the legal threshold limit on the amount of a substance allowed in public water systems as per the Safe Drinking Water Act.

The limit is usually expressed in a concentration of milligrams or micrograms per liter of water. These standards are set by the EPA for our drinking water quality. In order to set an MCL, the EPA first looks at what levels a contaminant can be present with no adverse health issues. That level is called the maximum contaminant level goal, which in a non-enforceable goal. The MCL is set as close as possible to the goal, but this system is not perfect.

Science takes time. The EPA sets standards based on the science available. Maybe they know that studies are coming out that a contaminant could cause cancer, so they set a goal or a health advisory, not an MCL. In other cases, they may have animal studies but not human ones. They can’t set standards until they understand the full impact for us. They can’t create regulations without the right amount of data. It’s a slow dance of completing the studies we need to create the right rules and regulations.

“We learned about GenX and other PFAS in our tap water six years ago,” said Emily Donovan, co-founder of Clean Cape Fear in a statement. “I raised my children on this water and watched loved ones suffer from rare or recurrent cancers. No one should ever worry if their tap water will make them sick or give them cancer. We will keep fighting until all exposures to PFAS end, and the chemical companies responsible for business-related human rights abuses are held fully accountable.”

While it’s good news to have regulations now in place and funding to support these changes, we must never forget that these toxic chemicals are byproducts of industry—chemicals used to make carpets, clothing, fabric protectors, paper packaging, and nonstick cookware.

The final rule requires:

Public water systems must monitor for these PFAS and have three years to complete initial monitoring (by 2027), followed by ongoing compliance monitoring. Water systems must also provide the public with information on the levels of these PFAS in their drinking water beginning in 2027.

Public water systems have five years (by 2029) to implement solutions that reduce these PFAS if monitoring shows that drinking water levels exceed these MCLs.

Beginning in five years (2029), public water systems that have PFAS in drinking water which violates one or more of these MCLs must take action to reduce levels of these PFAS in their drinking water and must provide notification to the public of the violation.

How You Can Protect Your Water From PFAS

Even bottled water can contain these toxic PFAS chemicals. While no treatment option is perfect, and none is likely to remove all PFAS, some treatment is better than none.

Your best option is to rely on the same technologies that treatment facilities will be using:

Activated carbon is similar to charcoal. Like a sponge, it will capture the PFAS, removing it from the water. This is the same technology in refrigerator filters and in some water pitcher filters, like Brita or PUR. Note that many refrigerator manufacture’s filters are not certified for PFAS, so don’t assume they will remove PFAS to safe levels.

Ion exchange resin is the same technology found in many home water softeners. Like activated carbon, it captures PFAS from the water, and you can find this technology in many pitcher filter products. If you opt for a whole house treatment system, which a plumber can attach where the water enters the house, ion exchange resin is probably the best choice. But it is expensive.

Reverse osmosis is a membrane technology that only allows water and select compounds to pass through the membrane, while PFAS are blocked. This is commonly installed at the kitchen sink and has been found to be very effective at removing most PFAS in water. It is not practical for whole house treatment, but it is likely to remove a lot of other contaminants as well.

(Source: The Conversation)

Let us know what you think about these brand-new PFAS regulations in the comments below. Are you relieved? What do you think about the timeline and funding?